Artist Samantha Wall at Stella Jones Gallery by Jeri Hilt

| The American South has been inundated with the stories and likenesses of the mulatto and—if you’re in Louisiana—Creole characters. Portrayals of multi-racial women specifically have ranged from substantial and transformative to exploitative and vapid. As an African American woman—with a cultural understanding that nearly all of the African American community has mixed ancestry of variant degrees—I found the portraits of multi-racial women in Wall’s exhibition, Indivisible, arresting if not remarkable. There is an undeniable universality in their likenesses. These were women I recognized, both for the distinct traces of their various ethnicities, and for the laughter and vulnerability in their expressions. Completely distinct and apart from their racial composition, the subjects of Wall’s exhibit are portrayed in their truth. In this way, Wall’s portraits challenge the socially constructed tiers of beauty ascribed to women of color—with beauty being determined, externally, on a scale of lightest to darkest with a predilection for European features. When asked about the impulse behind her art she explains that themes of identity will most likely stay with her work for a long time to come. “I’m interested in the ways shame operates in society,” says Wall. |

In our interview she discussed the palpability of shame, and it’s evidence in her own life. For Wall, this concept has been linked more directly with the country of her birth. Born in Korea and relocated to the U.S. at the age of four, Samantha Wall moved around quite a lot, and resided in Fort Jackson, South Carolina for most of her childhood. For a time Wall never questioned her parentage and believed that her white stepfather, also the father of her siblings, was also her father. However, in 2009 Wall took a DNA test, and discovered that her father was a man of African descent. Traces of European and Native ancestry would imply that he is also, most likely African American.

Samantha explained that finding out her father’s ethnic background was significant in ways that she had not anticipated. Even before she knew that she was both Korean and African, Wall describes feeling lobbied between cultural groups rather than feeling a part of them. This confluence and fracturing of identity is an observable theme in this collection.

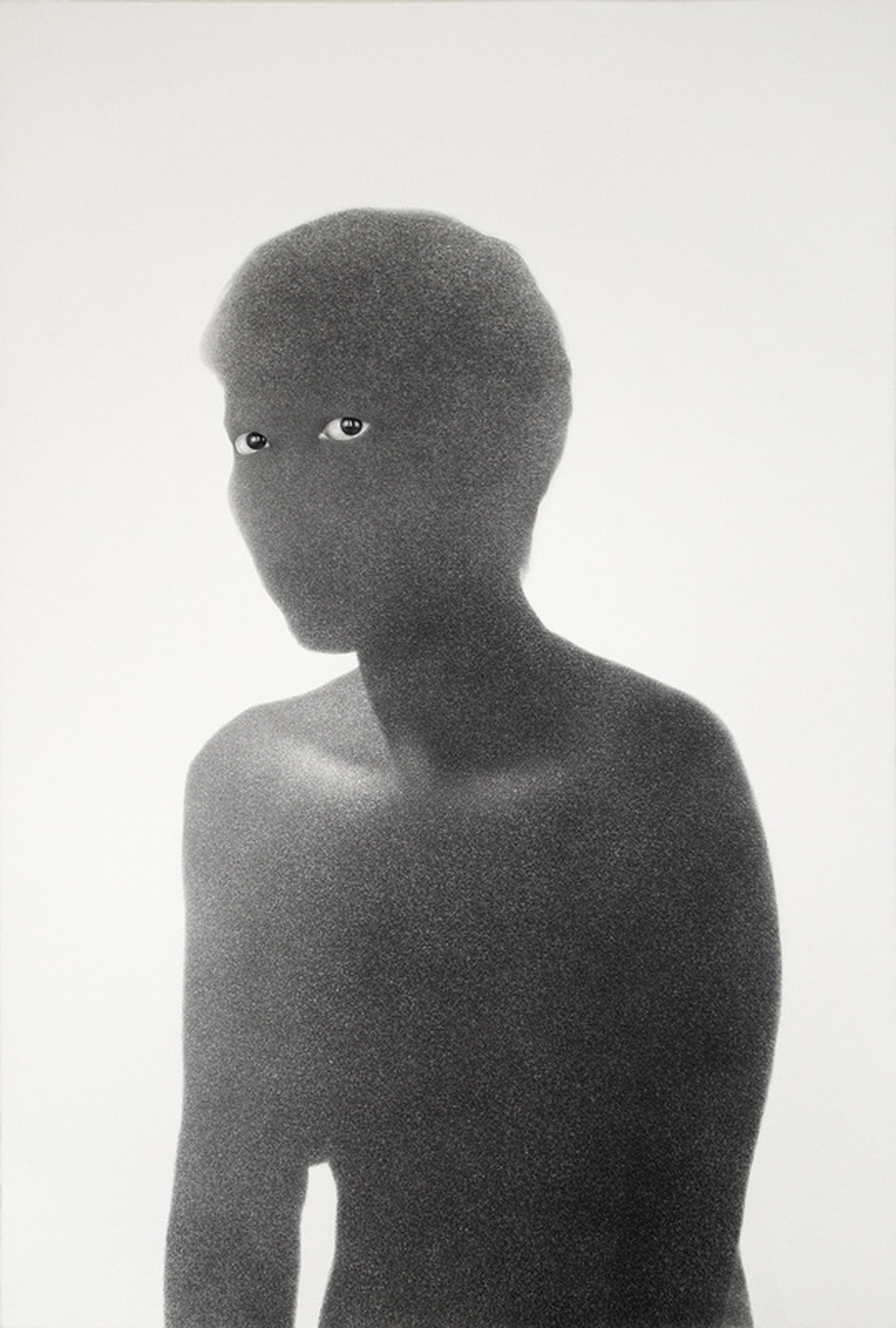

Included in her show is an astonishing self-portrait. Only her eyes are visible to the viewer, while the rest of her own image is a silhouette blacked out in charcoal. The title of the portrait, What I Can’t See, reveals what is otherwise invisible to the viewer, and Samantha herself. This level of honesty and vulnerability in art and the socio-political constructs of race forces us all to reconcile its incongruence, and the falsities embedded in who we perceive both ourselves and each other to be—especially when those perceptions are based on phenotypic observations.

Wall’s art exposes and deconstructs socially and politically constructed barriers that regularly impact how we engage with individuals of color. The presence of her work in New Orleans exposes and reveals these concepts in another environment. The portraits belie the inaccuracy and conceptual limitations of deeply entrenched notions of race and ethnicity. As an artist of color who is also a woman, our greatest artistic challenge is to represent women of color, however they identify, in their complete humanity. For Wall to accomplish this in a two-dimensional art form is both rare and exceptional. More than portraits, her work renders all women visible in liberating ways, Indivisible.

Samantha explained that finding out her father’s ethnic background was significant in ways that she had not anticipated. Even before she knew that she was both Korean and African, Wall describes feeling lobbied between cultural groups rather than feeling a part of them. This confluence and fracturing of identity is an observable theme in this collection.

Included in her show is an astonishing self-portrait. Only her eyes are visible to the viewer, while the rest of her own image is a silhouette blacked out in charcoal. The title of the portrait, What I Can’t See, reveals what is otherwise invisible to the viewer, and Samantha herself. This level of honesty and vulnerability in art and the socio-political constructs of race forces us all to reconcile its incongruence, and the falsities embedded in who we perceive both ourselves and each other to be—especially when those perceptions are based on phenotypic observations.

Wall’s art exposes and deconstructs socially and politically constructed barriers that regularly impact how we engage with individuals of color. The presence of her work in New Orleans exposes and reveals these concepts in another environment. The portraits belie the inaccuracy and conceptual limitations of deeply entrenched notions of race and ethnicity. As an artist of color who is also a woman, our greatest artistic challenge is to represent women of color, however they identify, in their complete humanity. For Wall to accomplish this in a two-dimensional art form is both rare and exceptional. More than portraits, her work renders all women visible in liberating ways, Indivisible.

Samantha Wall lives and works in Portland, Oregon. She is married to video and installation artist Stephen Slappe. For more information about her work visit: www.samanthawall.com. Wall's exhibit is part of the 4th Annual New Orleans Loving Festival and will run through July 31st at Stella Jones Gallery - 201 St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans, LA. www.stellajonesgallery.com

Jeri Hilt is a former lecturer of African Studies and International Development issues at Tennessee State and Dillard Universities. She has also worked with research, development, and teaching projects in South Sudan, Kenya, Burundi, and the United Kingdom. Hilt, a Louisiana native, currently teaches literacy intervention at an elementary school in New Orleans.

#lovingfestival

Jeri Hilt is a former lecturer of African Studies and International Development issues at Tennessee State and Dillard Universities. She has also worked with research, development, and teaching projects in South Sudan, Kenya, Burundi, and the United Kingdom. Hilt, a Louisiana native, currently teaches literacy intervention at an elementary school in New Orleans.

#lovingfestival

RSS Feed

RSS Feed